There are many reviewers and writers who have said that a good book is just that, a good book and it really doesn’t matter if the agents and publishers put the book out there as a children’s book or one for adults. I agree with that point of view and indeed have several ‘children’s’ books on my shelves that are precious to me and are worthy of my time reading and re-reading.

Geoffrey Trease was an early 20th century writer of historical fiction aimed at children. He made the way clear for others, in particular Cynthia Harnett and then the much revered Rosemary Sutcliff who breathed life into the characters of Roman Britain in her Eagle of the ninth sequence of novels. All these works were marketed as being suitable for ‘bookish children.’ In reality this meant that the reader had to have a very competent level of reading and the stamina to cope with a book of several hundred pages and no pictures!

Most people would agree that within this genre, the 1970s belonged to Barbara Willard and her Mantlemass stories. Regular readers will know that I love to get totally engrossed in a story that continues from book to book and generation to generation. Barbara Willard certainly works for me. Mantlemass is a family saga which has more in common with the Forsytes and the Pallisers than with Swallows and Amazons. This family feels real. All the endings are not necessarily happy and historical events ripple out and impact on this small community.

Barbara Willard was a particularly private person who shunned publicity. She lived near Lewes in Sussex and set her stories in the Ashdown Forest (but no sign of Pooh Bear or Piglet here). She worked as a trustee of the forest for many years and was instrumental in enabling the East Sussex Council to become involved in its management, thereby securing permanent public access to the forest.

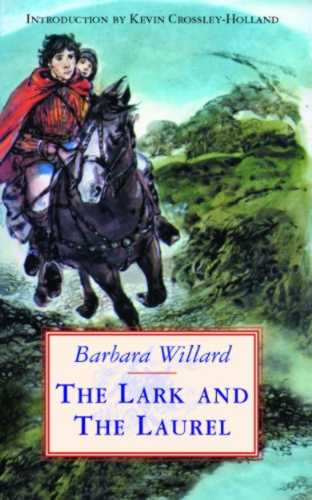

The first book: The Lark and the Laurel, starts at the birth of the Tudor age,1485 when the Battle of Bosworth changes the course of British history and the story then continues within the same physical setting for the next two centuries. At the beginning our heroine is Cecily Jolland and I’m sure, like me, you will warm to her and gradually come to love her as her life unfolds. I always think that it is absolutely necessary to care about at least one character in a book, otherwise why would you bother to keep turning the pages. Cecily is, without notice or explanation, ripped from her privileged London life, where her maid dresses her each morning and immediately attends to her slightest whim, to be thrust screaming into the household of her aunt who lives a country life in the Ashdown forest. Cecily’s only understanding of the situation is that her father backed the losing side in the battle between Lancaster and York and now feels he must go to France with all possible haste. A daughter would simply be an encumbrance.

Obviously, through time, there have always been strong, independent women, even when laws, manners and etiquette were against them. It is however immensely refreshing to have these characters at the forefront of a story, instead of at the edges. Dame Elizabeth (Cecily’s aunt) is one such and she intends to instill the required confidence, knowledge and spirit into her niece Cecily.

Barbara Willard deftly moves her character forward as Cecily’s appearance, attitude and thoughts become more ‘foresty’ and the girl reconsiders her earlier London life as pampered and superficial. Dame Elizabeth is determined to teach the child to read and write as well as how to churn butter and stretch rabbit pelts. The author employs quite a lot of regional forest vocabulary which I rather enjoy and certainly gives a strong sense of place. The story is written with a fast-paced denouement which is satisfying in itself but also leaves me eager for the next volume.

Researching around this writer and her work, I came across a well written review from the Times Literary Supplement which ends thus: …’ Are they (the Mantlemass Chronicles) children’s books? They are books for readers. They explore some of the basic themes of all literature: life, death, love, heredity, work.’ That says it all I think.

If I am recommending a book to you, I always feel that I should ensure you can get hold of it if you wish. I ventured onto Amazon rather apprehensively as I really didn’t know if The Lark and the Laurel would still be in print. As it happens it is, as well as the several sequels. A pleasant surprise indeed. Sadly, I don’t think they will be on the shelves of many school libraries these days.