I wonder where you were in the winter of 1962/3? I was in Sevenoaks in Kent and I have a clear memory of pressing my nose to a very cold window and trying to count the snowflakes as they started to fall. This was the evening of Christmas Eve and I remember thinking that this was very right and proper; the way it should be. We would have a white Christmas. Well, we did but really the snow started to fall with an unstoppable intensity on Boxing Day.

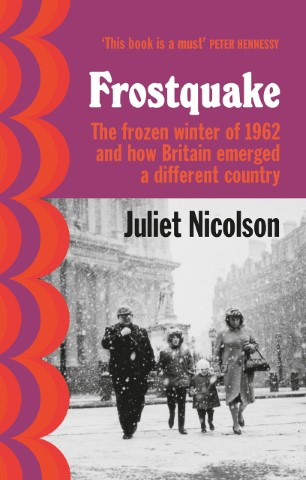

This desperately hard winter forms the basis for Juliet Nicolson’s book called Frostquake. As well as thinking about her own family experiences of that particular winter she works her way through many of the parochial and global events that happened at that time. Thus we are reminded of the Profumo Affair and all the links with Cliveden, eventually bringing down Macmillan’s Tory government. I hadn’t really been aware that it was Macmillan who made the first rather tentative advances to make Britain a member of the EEC (as the EU was then known) and that de Gaulle had been firmly against the idea. The Cuba crisis took place then with all the ramifications and tensions of possible nuclear war and the Beatles were becoming more popular than anyone had thought possible.

I knew I would enjoy reading the book because I lived through it and I become ever more fascinated by the history of the 20th century but there is of course more to it than that. It is somewhat bemusing to realise how different life was then. The contraceptive pill was just becoming available but to begin with to married women only. The equal pay act was still many years away as was the Wolfenden act, legalising homosexuality. This made the scandal involving Jeremy Thorpe into something possibly unlawful and popularly considered immoral. Today, nobody would be really very interested I think.

The concept of ‘the teenager’ had come into popular usage maybe in the late 1950s, usually used rather disparagingly, but in the early 1960s youth culture exploded. The Beatles, the Rolling Stones (far too scary and rude for most girls in my friendship group), the Hollies and many more, gave young people their own music and designers such as Mary Quant powerfully influenced what they wore. No longer did girls go from school uniform straight to wearing suits and twin sets just like their mothers. Tights were amazingly only just coming into the shops and I definitely remember getting to school that winter with red, raw legs and indeed totally numb feet from wearing wellington boots. No fun at all. Boys of primary school age all wore shorts, pulling their long grey socks up over their knees to make the cold, bare gap of leg smaller. My school did not close at all despite inefficient heating, frozen bottles of milk by the classroom door and a sloping playground that became an ice slide. Nobody stopped us playing on it! Everything was more local then with virtually all the children and indeed staff living within walking distance.

In the arts, I find it hard to believe that the act repealing theatre censorship did not take place until 1968 but despite that, people were pushing hard at the boundaries by 1963. The TV programme ‘That was the week that was’, fronted by David Frost and Ned Sherrin quickly became known as TW3 and was loved and reviled in equal proportion. I never watched it, being way past my bedtime and probably considered by my parents as rather risqué. Such programmes brought the likes of Mary Whitehouse into the public eye although she did not get properly organised until a few years later.

Juliet Nicolson can only be congratulated on the vast amount of research she undertook for this book. However, the style she employs I find slightly uncomfortable. She links one example to another, and another, and sometimes it can feel like a list, linked together with very loose stitches. It would not have been an acceptable style when I was doing A level English years ago. Despite this I enjoyed the book. It brought back many memories and heightened my awareness of early 1960s history. If this book works for you, there are more. One that I have read is about the year 1911 and there is also one about the abdication in 1936.

My second book could not be more different: The Pottery Gardener by Arthur Parkinson. It is a feast for the eyes even if you don’t read a word but personally I find the prose as colourful and delightful as the vivid pictures of tulips, dahlias etc. His story is interesting I think. Having trained at Kew, he visited Perch Hill in Sussex where he talked to Sarah Raven and ended the day with the offer of a summer job. (If you haven’t been to Perch Hill do put it on your list of places to go, when we are allowed of course.) He obviously impressed, because when Emma Bridgewater got in touch with Sarah Raven about the possibility of building a garden on her factory site in Stoke on Trent, it was Arthur who was despatched to do the job. And wow did he do it well as the pages of colour testify. I recommend this to you as a piece of pure joy and I think we can all use that right now.

I had been thinking that there was no con-nection between these two books but I realise there is and it is the Nicolson family of Sissinghurst, home of the late Vita Sackville West. Juliet Nicolson is a granddaughter of Vita and sister of Adam Nicolson, whose wife is Sarah Raven, gardening muse of Arthur Parkinson!